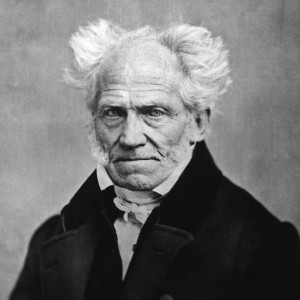

Arthur Schopenhauer quotes - page 10

Arthur Schopenhauer was a German philosopher known for his work on pessimism and the nature of human desire. His major work, "The World as Will and Representation," greatly influenced existentialist and psychoanalytic thought. He is remembered for his profound impact on later philosophers and for shaping modern philosophical discourse. Here are 353 of his quotes:

Compassion for animals is intimately connected with goodness of character, and it may be confidently asserted that he, who is cruel to living creatures, cannot be a good man. Moreover, this compassion manifestly flows from the same source whence arise the virtues of justice and loving-kindness towards men.

Arthur Schopenhauer

It is asserted that beasts have no rights; the illusion is harboured that our conduct, so far as they are concerned, has no moral significance, or, as it is put in the language of these codes, that "there are no duties to be fulfilled towards animals." Such a view is one of revolting coarseness, a barbarism of the West, whose source is Judaism. In philosophy, however, it rests on the assumption, despite all evidence to the contrary, of the radical difference between man and beast,-a doctrine which, as is well known, was proclaimed with more trenchant emphasis by Descartes than by any one else: it was indeed the necessary consequence of his mistakes.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Europeans are awakening more and more to a sense that beasts have rights, in proportion as the strange notion is being gradually overcome and outgrown, that the animal kingdom came into existence solely for the benefit and pleasure of man. This view, with the corollary that non-human living creatures are to be regarded merely as things, is at the root of the rough and altogether reckless treatment of them, which obtains in the West.

Arthur Schopenhauer

A mother gave her children Aesop's fables to read, in the hope of educating and improving their minds; but they very soon brought the book back, and the eldest, wise beyond his years, delivered himself as follows: This is no book for us; it's much too childish and stupid. You can't make us believe that foxes and wolves and ravens are able to talk; we've got beyond stories of that kind! In these young hopefuls you have the enlightened Rationalists of the future.

Arthur Schopenhauer

His [the Philistine's] existence is not animated by any keen desire for knowledge and insight for their own sake, or by any desire for really aesthetic pleasures which is so entirely akin to it. If, however, any pleasures of this kind are forced on him by fashion or authority, he will dispose of them as briefly as possible as a kind of compulsory labour.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Spinoza says that if a stone which has been projected through the air, had consciousness, it would believe that it was moving of its own free will. I add this only, that the stone would be right. The impulse given it is for the stone what the motive is for me, and what in the case of the stone appears as cohesion, gravitation, rigidity, is in its inner nature the same as that which I recognise in myself as will, and what the stone also, if knowledge were given to it, would recognise as will.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Thus, because Christian morals leave animals out of consideration ... therefore in philosophical morals they are of course at once outlawed; they are merely "things," simply means to ends of any sort; and so they are good for vivisection, for deer-stalking, bull-fights, horse-races, etc., and they may be whipped to death as they struggle along with heavy quarry carts. Shame on such a morality ... which fails to recognize the Eternal Reality immanent in everything that has life, and shining forth with inscrutable significance from all eyes that see the sun!

Arthur Schopenhauer

The cheapest form of pride however is national pride. For it reveals in the one thus afflicted the lack of individual qualities of which he could be proud, while he would not otherwise reach for what he shares with so many millions. He who possesses significant personal merits will rather recognise the defects of his own nation, as he has them constantly before his eyes, most clearly. But that poor blighter who has nothing in the world of which he can be proud, latches onto the last means of being proud, the nation to which he belongs to. Thus he recovers and is now in gratitude ready to defend with hands and feet all errors and follies which are its own.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Every true thinker for himself is so far like a monarch; he is absolute, and recognises nobody above him. His judgments, like the decrees of a monarch, spring from his own sovereign power and proceed directly from himself. He takes as little notice of authority as a monarch does of a command; nothing is valid unless he has himself authorised it. On the other hand, those of vulgar minds, who are swayed by all kinds of current opinions, authorities, and prejudices, are like the people which in silence obey the law and commands.

Arthur Schopenhauer

If you try to imagine, as nearly as you can, what an amount of misery, pain and suffering of every kind the sun shines upon in its course, you will admit that it would be much better if, on the earth as little as on the moon, the sun were able to call forth the phenomena of life; and if, here as there, the surface were still in a crystalline state.

Arthur Schopenhauer

My basis is supported by the authority of the greatest moralist of modern times; for such, undoubtedly, J. J. Rousseau is,-that profound reader of the human heart, who drew his wisdom not from books, but from life, and intended his doctrine not for the professorial chair, but for humanity; he, the foe of all prejudice, the foster-child of nature, whom alone she endowed with the gift of being able to moralise without tediousness, because he hit the truth and stirred the heart.

Arthur Schopenhauer

University professors, restricted in this way, are quite happy about the matter, for their real concern is to earn with credit an honest livelihood for themselves and also for their wives and children and moreover to enjoy a certain prestige in the eyes of the public. On the other hand, the deeply stirred mind of the real philosopher, whose whole concern is to look for the key to our existence, as mysterious as it is precarious, is regarded by them as something mythological, if indeed the man so affected does not even appear to them to be obsessed by a monomania, should he ever be met with among them. For that a man could really be in dead earnest about philosophy does not as a rule occur to anyone, least of all to a lecturer thereon; just as the most sceptical Christian is usually the Pope. It has, therefore, been one of the rarest events for a genuine philosopher to be at the same time a lecturer in philosophy.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Epicurus, the great teacher of happiness, has correctly and finely divided human needs into three classes. First there are the natural and necessary needs which, if they are not satisfied, cause pain. Consequently, they are only victus et amictus [food and clothing] and are easy to satisfy. Then we have those that are natural yet not necessary, that is, the needs for sexual satisfaction. ... These needs are more difficult to satisfy. Finally, there are those that are neither natural nor necessary, the needs for luxury, extravagance, pomp, and splendour, which are without end and very difficult to satisfy.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer

Occupation: German Philosopher

Occupation: German Philosopher

Born: February 22, 1788

Died: September 21, 1860

Quotes count: 353

Wikipedia: Arthur Schopenhauer